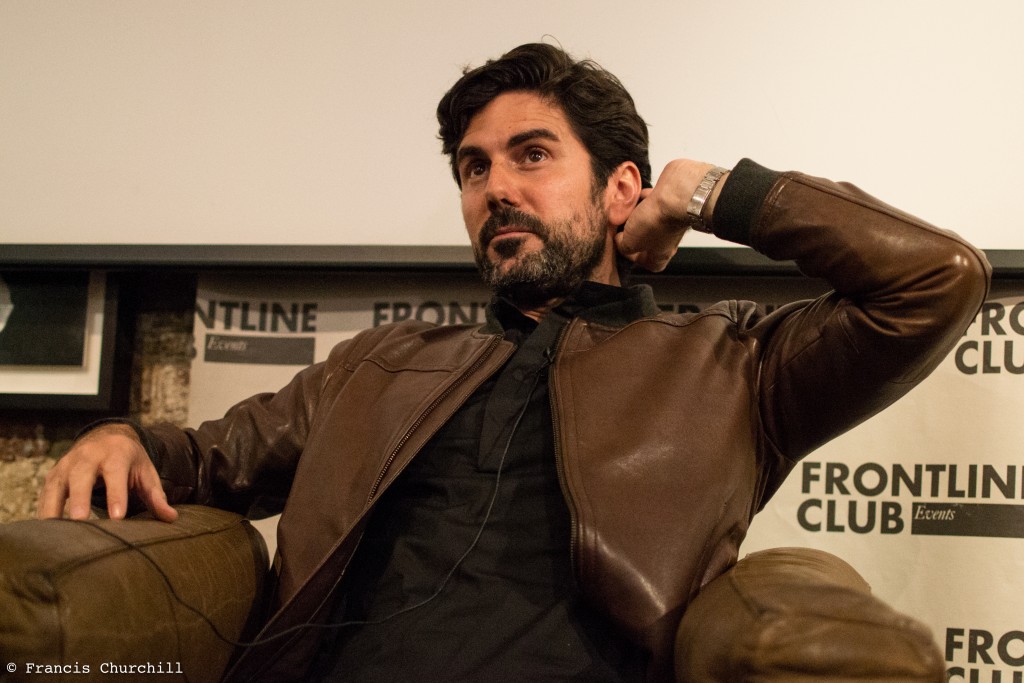

UK Premiere of Born in Gaza

Zin said he wanted to show a different side of war: “Sometimes I feel like we’re always running with the camera behind, you know… That’s why I say OK, I’ll do just the opposite. A different perspective; no bombs, no dead bodies. And secondly, very slowly. Even though it was in the middle of a war, we tried to get inside the people, because I think that the consequences of war are inside the people… We miss that in normal journalism.”

“I was a little bit like a madman… [Other journalists] were running in one direction to the bombs with the flack jacket and the helmet and I was going in the other direction with my swimming trunks,” said Zin, referring to the scenes shots in the sea off the beaches of Gaza.

The film was constructed around a set of candid interviews with a group of children who had been deeply affected by the conflict.

“I wasn’t very sure if that was going to work, if they had enough speech to keep a 70 minute-long movie, just with their own voices and thoughts. But it worked,” said Zin, who was surprised at how well his subjects understood their own situation.

“They know so well that… across the Mediterranean, children in Spain, Italy, in Greece, were playing in the beach,” said Zin.

“We had everything translated three times because I was so surprised, how come they’re speaking like this?… They want to take things into their own hands, because when they look up at their parents and grandparents, [they think that] somehow they’ve not protected them.”

“They are not happy about their leaders,” said Zin, referring to Hamas and Fatah, “…sometimes the Palestinians blame first their leaders and then the Israelis.”

A number of audience members asked how he was able to create the film without inflicting more psychological damage on the children interviewed. In one scene in particular, Zin takes the two boys who survived the infamous airstrike that that killed four children from the same family back to the same beach for the first time since the event.

“I didn’t want to make them suffer and bring back the trauma. But somehow one of the fathers said, ‘OK, they have to go back sooner or later so let’s go’,” said Zin.

“Sometimes for respect, and of course not wanting to bring the trauma back to people, we push them aside. And if they have the need to talk, or if they trust you and they want to talk, let’s treat them normally.”

Another audience member was interested to hear how Zin found the experience of working in Gaza, both during the war and when he visited three month later. Permits to enter Gaza are given and taken away very arbitrarily by the Israeli authorities, Zin said, but during the conflict he was free to move as he wished. This had its dangers though.

“Israeli drones are 24 hours a day, flying over you. You can listen to them and during sunset, with the way the light comes, you can see them… We were trying to move ourselves very slowly, showing we are not doing anything [bad]. But we were very scared,” said Zin.

Zin said he feels an obligation to show the film to as many audiences as possible, from Canada to India, and would also like to see the film screened in Israel. “There is a huge swathe of Israelis who would love to see this,” commented one audience member in agreement.

For Zin, there is also a real sense of urgency. “I would like people to see this before the next time they feel tempted to throw rockets at Gaza again,” he said.

Visit the Born in Gaza Facebook page for more information on the film and upcoming screenings.