John Pilger and The Wars We Don’t See

By Christopher Czechowicz

As a daring and impassioned journalist with a decades-long career, John Pilger has inspired and motivated many to ensure human rights and preserve unfiltered truth.

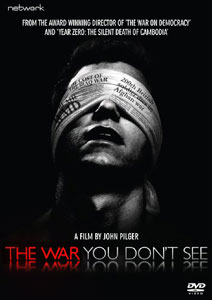

From films such as Year Zero: The Silent Death of Cambodia (1979) to The New Rulers of the World (2001), he has unrelentingly made this his commitment. This continues with his newest film, The War You Don’t See (2010). In this work, Pilger masterfully presses against those who weaken journalism’s efficacy in the current political climate.

Complementing previous works such as Noam Chomsky’s book on media manipulation, Manufacturing Consent (1988), and Adam Curtis’s films on mass psychology and the politics of fear, The Century of the Self (2002) and The Power Of Nightmares (2004), Pilger lends his experience in media to answer similar questions posed in those works about the role of public relations and media in war, journalists in the advancement of a war agenda and the reporting of war crimes. At its conclusion, the message is and clear: when searching for the truth, always challenge the official story.

Truth be told, The War You Don’t See is remarkably relevant to today’s world. At first, Pilger’s effort details the history of public relations and fuses it with the current backdrop of the dual wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Concepts such as propaganda and media manipulation are analysed as means of conveying official truths about war.

In a tense and demanding manner, the film’s images of bullet-riddled buildings, explosions and death in Baghdad, Kabul and Palestine shatters the viewer’s outlook on mainstream media like glass. Interviews are conducted in a powerful face-to-face manner that pulls no punches. To that end, it includes a soundtrack of simple yet beautiful orchestral passages that add to the film a solemn character. In total, it makes The War You Don’t See offers a rewarding viewing experience will be detailed more greatly below by theme.

Public Relations: The Facts Don’t Matter Anymore

In The War You Don’t See, the early machinery of media propaganda is detailed at length. From the 1910’s and 20’s work of Walter Lippmann and Edward Bernays, who improved techniques of public relations during the First World War to the Bush and Blair “Shock and Awe” doctrine of in the Iraq invasion of 2003, an understanding of the role of social psychology acts as a foundation to Pilger’s argument.

War Drums Beating

With UK/US official narratives, press releases and statements intertwining with the supposed objective reporting of Western media, the co-opting of the Fourth Estate for official purposes becomes apparent. In his familiar manner of grilling those in power, Pilger highlights government-PR inspired news and the media circus that it generates.

“…I’m not the vice-president in charge of excuses“ – a former CBS anchor Dan Rather

With the cordial commentary and praise of American and British journalists about their country’s leadership in times of hardship, the interest of media to portray conflicts in a favorable manner to governments and business is apparent.

Embedding or In Bed?: Journalists in the Game and Made for TV moments

“…I didn’t really do my job properly. …One didn’t press the most uncomfortable buttons hard enough…” – Rageh Omaar, former BBC world affairs correspondent

According to the film, current wars instigate media circuses and plenty of carefully orchestrated photo ops. In the run up and early years of the Iraq war, the mainstream media appears as a complicit tool of elite power interests, backing prevailing government views despite dissent or independent journalism that strayed from pro-war narratives, or their accompanying iconic images.

Everlasting Images

In occupied Iraq, the tumbling of Saddam’s statue in Baghdad and the placing of an American flag on his head “…gave no sense of the bloody conquest of Iraq that was already underway.” Against the jubilation and news clips of war proponents glorifying American weapons and military might, Pilger places shots of buildings in ruins, adults facing hardship and wounded and killed children.

Independent Journalism Vs. the “Propaganda of Fear”?

Like in his other films, another motif common to the work is the scale of suffering of ordinary people. To that effect, the work of independent journalists Mark Manning and Rana al Aiouby‘s during the Battle of Fallujah, Iraq is featured. It deviates from the official and mainstream portrait of events, using examples from history like Wilfred Burchett’s detail of an Atomic plague, or Dahr Jamail’s revealing and horrific footage of the torture of Iraqi citizens in the second Gulf War.

The propaganda of fear is described as having begun as early as the Vietnam War. To Pilger, it is “…the blueprint for the wars of today” in Afghanistan in Iraq. Pilger asserts: “…As in previous wars, public memory of the Vietnam war was greatly influenced by Hollywood”. In keeping with the tradition of films that aggrandise government war efforts, Iraq war movies attempt to inspire a masculine, aggressive, and staunchly supportive viewpoint of an occupation, with the on-screen Western powers nearly always championing a noble cause against a dim-witted and ultimately unsuccessful enemy effort.

“Modern democracies don’t leave marks” – Phil Shiner of Public Interest Lawyers

Other parts of the Wars We Don’t See also include soldiers abusing Iraqi civilians secretly on tape, as embedded journalism is the point of view of the troops, not the civilians. With that being the case, atrocities by coalition forces can be concealed, shrouding the views of afflicted peoples in official, sanitised manner. The disconnect between western audiences and those announced in death tolls is apparent, as the press “plays down the carnage”, and distinguishes between unworthy and worthy victims, with the latter bizarrely labeled peculiar for disapproving of having their houses invaded and loved ones killed.

A Major Deception

““If you look at every war, or every coup, or every regime that Britain is supporting or involved in…it’s usually accompanied by an increasingly sophisticated public relations operation by the Government…” – Mark Curtis, British historian

Another aspect of the invisible war includes no accountability of media personnel. Able to spit factoids or spin events, governments, acting as information machines, take the view that if journalists are not particularly supportive to their accounts, they could be frozen out of the access, as the apparatus “…would make life harder for them.” This implies why important dissenters to war aren’t heard, for example, Charles Hanley’s analysis of WMD sites and Scott Ritter’s detail of completely eliminated weapon sites in Iraq before Gulf War Two began.

The Narrative of Mainstream Journalism

Pilger encounters the reaction of mainstream media participants that seek to downplay any observed complicity. In this effort, he does not go unchallenged. ”It’s not up to me to make a judgment.” says one Britis

h journalist to Pilger. “We’re there to report what their claims are and hold them up to scrutiny, and to investigate.” Just the same, in this film, investigative journalism is portrayed as a bulwark against conflict.

Preventing wars?

As the film progresses, the media spin of governments is documented as an example of the War We Don’t See. In some countries, after a government crime is committed, intimidation from embassies not to reveal damaging information to host countries covering the incident is apparent. Spokesmen from guilty governments act as spinsters, offering official lies as truth, using doctored sources to strength their claims. Commentators convince the public to go along for the ride.

The UK and US Government reaction to WikiLeaks

According to Pilger, just as some governments spin the truth, the Obama Administration and British Ministry of Defence have attacked “truth-tellers” WikiLeaks, Julian Assange and others who deviate from the official narrative or spectrum of discourse and punditry. To stress this point, Pilger reveals a leaked secret British Government file which sees investigative journalists involved with the propagation of WikiLeaks’ source material as a threat to be neutralised by various means. Leaked material, such as the 2010 release of “Collateral Murder”, is described as an example The War You Don’t See.

“The Public is a threat that needs to be countered…”

"…The more information the public has, the more difficult it is for them (governments) to pursue policies that maybe are abusive of human rights or involving supportive a repressive regime.” – Mark Curtis, British historian

Perhaps what’s most important about this film is its simple message. For John Pilger, the mainstream Fourth Estate is not doing its job properly. Whereas independent journalists are able to articulate the truth in a sophisticated manner, mainstream sources remain disinterested in their work. Time and again, they prefer baseless information, sound bytes and sensational footage of clamoring crowds that rouse emotion to the hard tasks journalists must perform. In Pilger’s final remarks in the film, what remains clear is that more than ever, uncompromised, brave journalism is needed in our world, always challenging the official story, in his words, “however patriotic it appears, or however seductive or insidious it is.”