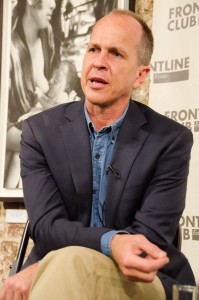

Beyond the limit: Peter Greste recounts a year in Egyptian prison

Out of the blue

Speaking to journalist Sue Turton, Greste recalled the otherwise ordinary evening in December 2013 when in the midst of his preparations to go out for dinner “about eight guys” burst into his room. They put him in handcuffs and took him to a police cell. He would not be free again for almost 14 months.

Greste, who was working for Al Jazeera English at the time, had experienced brushes with the authorities when working on controversial stories at other points in his career. But this time his arrest came completely out of the blue.

Greste, who was working for Al Jazeera English at the time, had experienced brushes with the authorities when working on controversial stories at other points in his career. But this time his arrest came completely out of the blue.

“We knew that we hadn’t done anything wrong; we hadn’t pushed any boundaries,” he said. “We’d always felt when we were working that as long as you play with a straight bat you’ll be relatively safe.”

Although Greste and his two Al Jazeera colleagues, Mohamed Fahmy and Baher Mohamed, forced themselves to consider the possibility that they would be convicted, they “never really believed it,” he said.

But on 23 June 2014, Greste was sentenced to a seven-year term on accusations of terrorism and inventing the news, based on courtroom evidence that included footage of a family holiday and stories wholly unrelated to Egypt. Fahmy was also given a seven-year sentence; Mohamed was given ten years.

Creating structure

Conditions in the Tora Mazraa prison on the outskirts of Cairo, where Greste and his fellow inmates were confined to cramped cells for 23 hours a day, were humane but basic.

In order to cope, Greste developed a daily regime that included meditation, exercise and rigid study.

“I had to make a conscious decision to stay fit: physically fit, psychologically fit, and spiritually fit,” he said.

“I had to make a conscious decision to stay fit: physically fit, psychologically fit, and spiritually fit,” he said.

Each day, Greste spent an hour running up and down the 30 metre corridor outside his cell, covering distances of up to 12 kilometres a day.

He began studying for a master’s degree in international relations, courtesy of Griffith University in Australia. The university delivered 13 kilograms of academic papers to the prison, where Greste studied in his cell with pencil and paper.

“I figured there was no way I’d be able to get through this without doing something with my mind,” he said. “Even when your physical integrity is at risk, what really matters is your own mind and how you cope with it.”

Setting a horizon

Even with these distractions, the mental side was the greatest challenge, said Greste.

“The biggest danger is that your own mind can run away and play all sorts of tricks on you,” he said.  “There were some really black days when you sink into despair, but you have to ride it out. If you carry a grudge with you it’s only going to turn in on yourself.”

“There were some really black days when you sink into despair, but you have to ride it out. If you carry a grudge with you it’s only going to turn in on yourself.”

The challenge was made all the more great by the uncertainty of the situation.

“The hardest part…was the open-ended nature of it,” said Greste. “Towards the end we knew we would probably have to mentally prepare for six more years.

“The only way through is to set your horizon to something you think you can cope with. Sometimes to the end of the week, or the next visit. Sometimes to the end of the day. Sometimes I’d say I’ll get through one more hour and I’ll think about the next hour after that then. It’s not easy, but it’s a matter of biting off the amount that you think you can chew.”

Emotional release

When Greste’s release came, it was sudden. “The embassy’s coming for you in an hour,” he was told. “Get your stuff you’re going home.”

At the time Fahmy was in hospital receiving treatment for an injured shoulder and Hepatitis C, but leaving behind Mohamed was an emotional moment for Greste.

“When you spend 400 days in a box with someone you get to know each other pretty well,” he said. “It’s as close as you can come to having a brother. Walking away and leaving them behind is not easy, and I still feel anguished about it.”

Greste attributed his release to the international pressure that was brought to bear on his behalf, both in the diplomatic community and in the media.

“I was rather spoiled,” he joked. “I had two governments on my case – Australia and Latvia. And I didn’t even know that I was Latvian!”

Ongoing campaign

Not everyone was so lucky. Many are still facing charges, said Greste, including a Dutch journalist and three young students who were attached to his case. Six Al Jazeera journalists, including Turton, were convicted in absentia.

Fahmy and Mohamed were released on bail on 13 February, after spending 411 days in prison, when an Egyptian court overturned an earlier verdict that had found them guilty of supporting the Muslim Brotherhood.

A retrial was scheduled for 23 February 2015, but has now been adjourned until 8 March.

The campaign to free Fahmy, Mohamed and the numerous other journalists who have been unjustly detained in Egypt and elsewhere, is ongoing.

Last year, 120 journalists were victims of targeted killings worldwide, the most dangerous countries including Pakistan, Syria, Ukraine, Honduras and Mexico, said Andy Smith, joint president of the UK’s National Union of Journalists, who joined the Frontline Club discussion for the latter stages.

Last year, 120 journalists were victims of targeted killings worldwide, the most dangerous countries including Pakistan, Syria, Ukraine, Honduras and Mexico, said Andy Smith, joint president of the UK’s National Union of Journalists, who joined the Frontline Club discussion for the latter stages.

The number of journalists imprisoned worldwide for doing their job has increased from roughly 100 at the turn of the century to about 200 today, said Smith.

Greste underlined the importance of not letting the pressure for media freedom ease up following his release.

“The [journalism] community across the globe pulled together in a way that was absolutely unprecedented,” he said.” “If we lose this unity of purpose we lose something of enormous value. It is incumbent on everyone to use this not just in our case but in the case of every journalist.”

There is a natural reticence among the journalism community to write about other journalists, said Greste, but this is something that must be overcome.

“Journalists covering journalists gets us in some sort of existential angst, but we need to recognise that it’s an essential part of society, we are the fourth estate. We’ve got to appreciate that an attack on journalism, on the freedom of speech, is an attack on wider society. We need to learn to be a little less self-conscious about covering the plight of journalists…because it tends to be a symptom of much deeper problems.”

Empowering

The other significant legacy of Greste’s ordeal was the discovery that his limits went far beyond his imagination.

“It has changed me as a person,” he said. “I’ve been tested and I’ve discovered that my limits are a lot further than I thought they were, and it’s a very empowering thing.

“I think most people are vastly more capable of dealing with difficult situations than you imagine.”

Watch and listen back below: